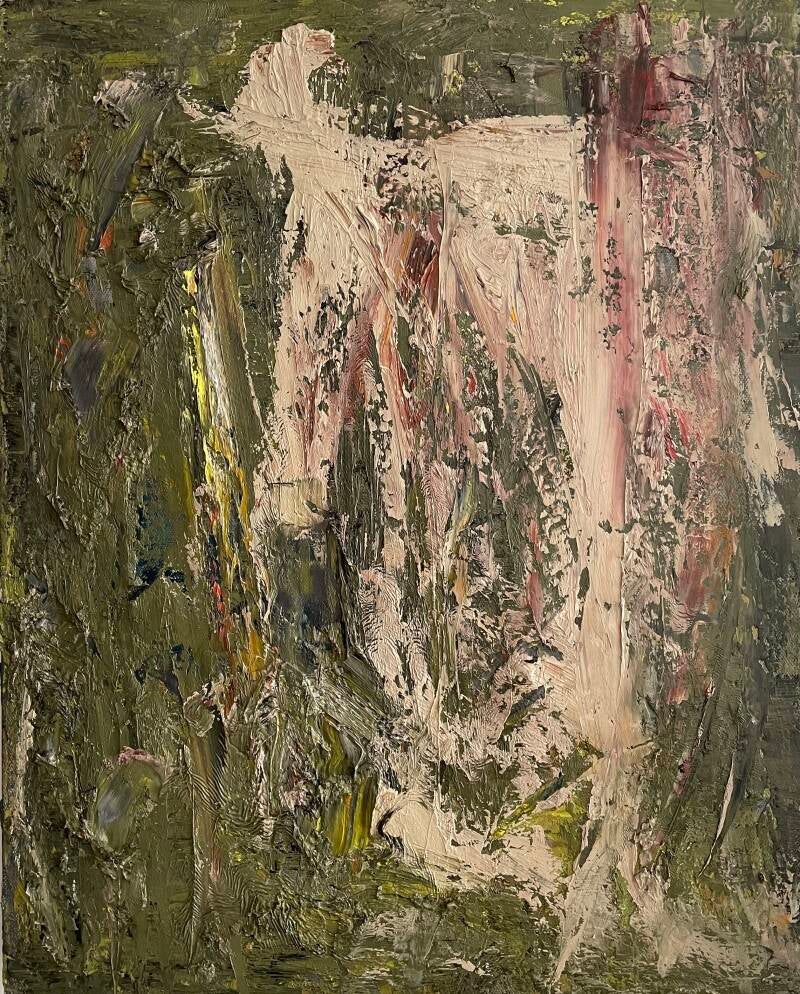

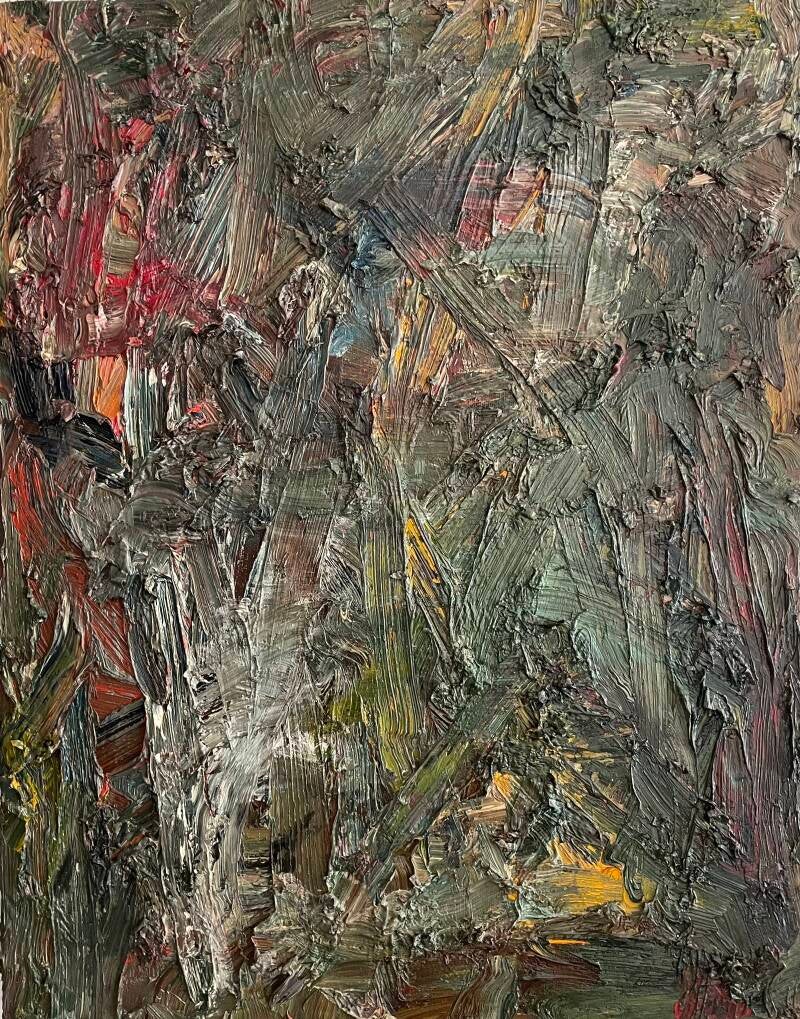

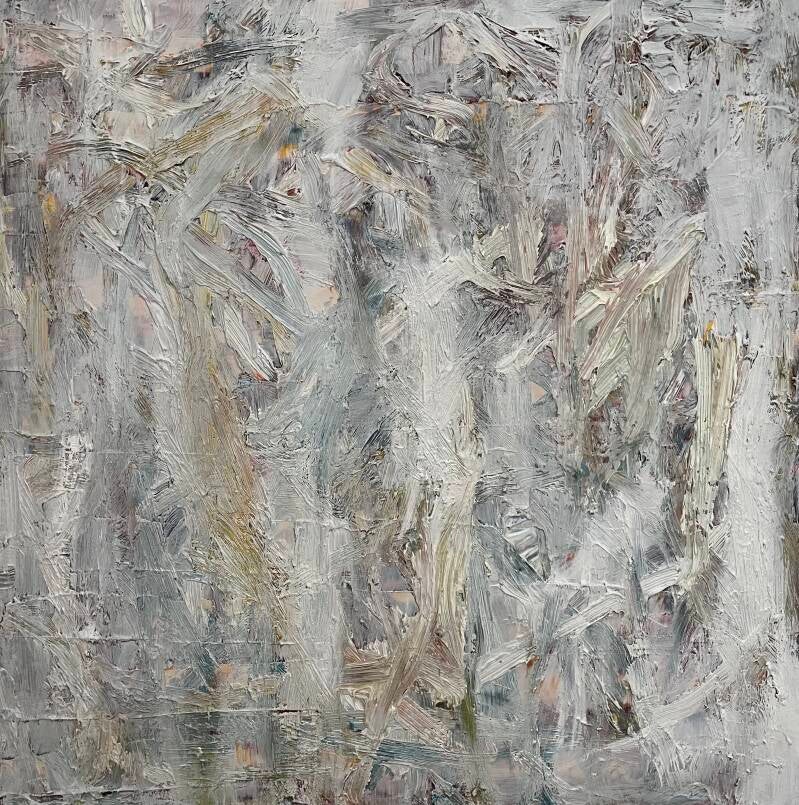

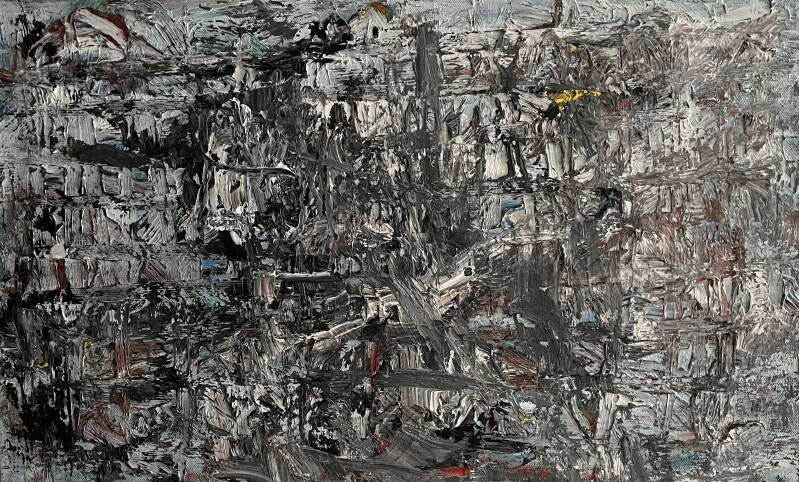

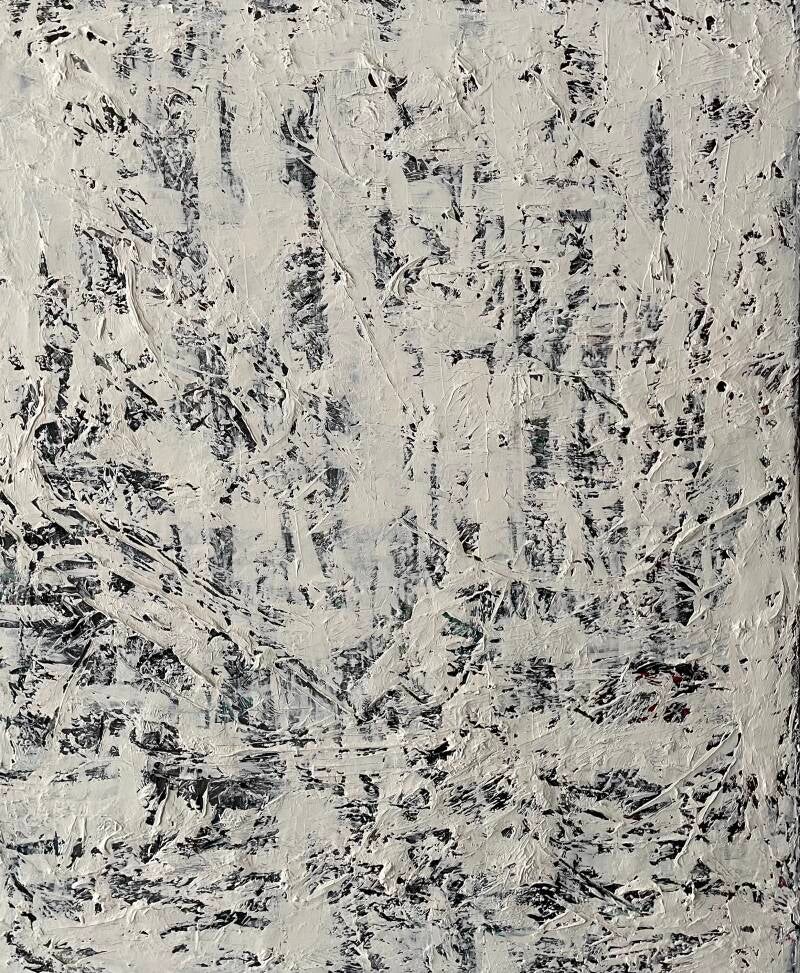

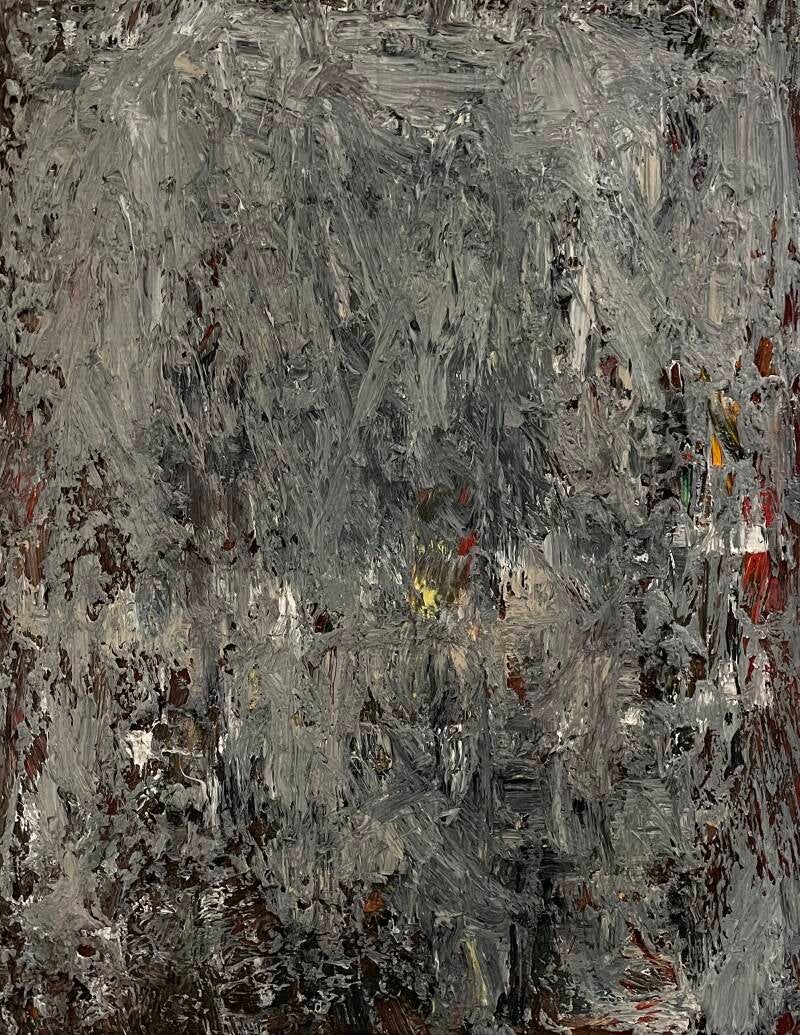

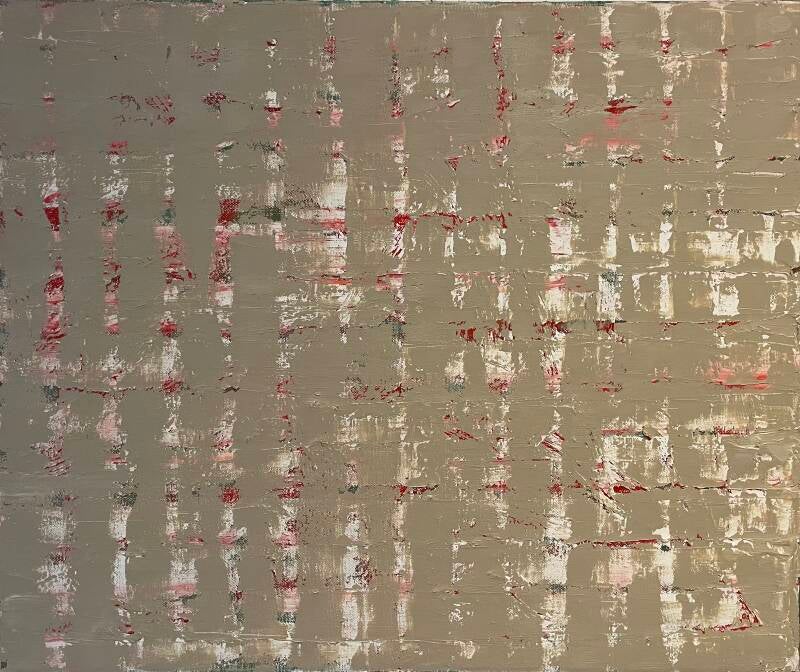

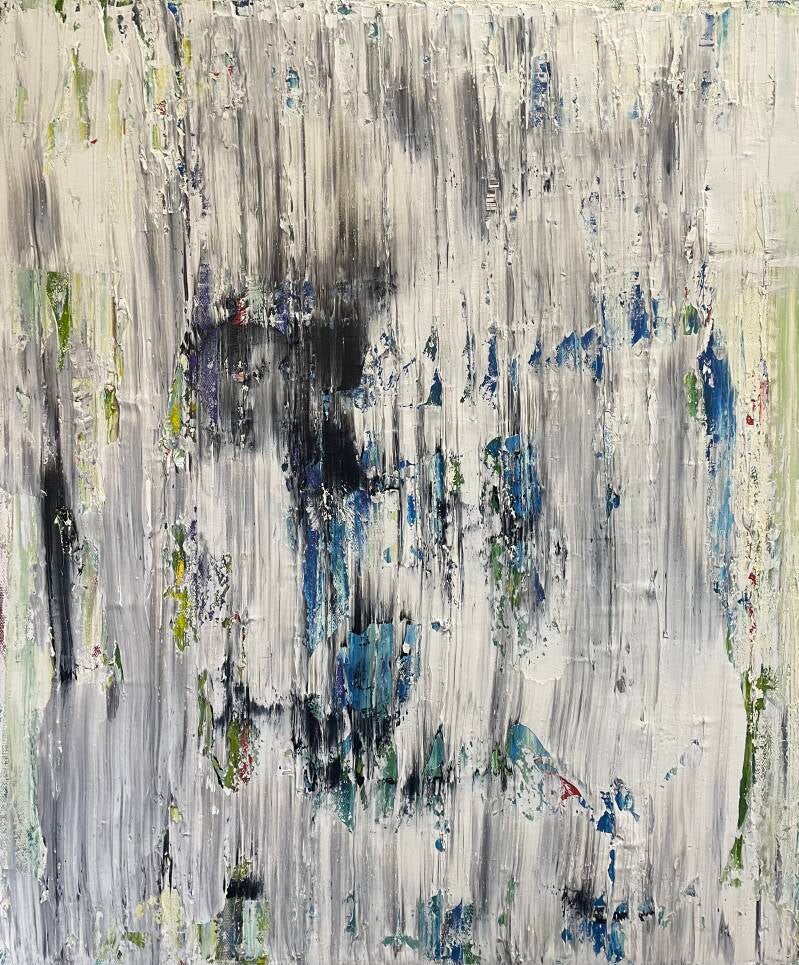

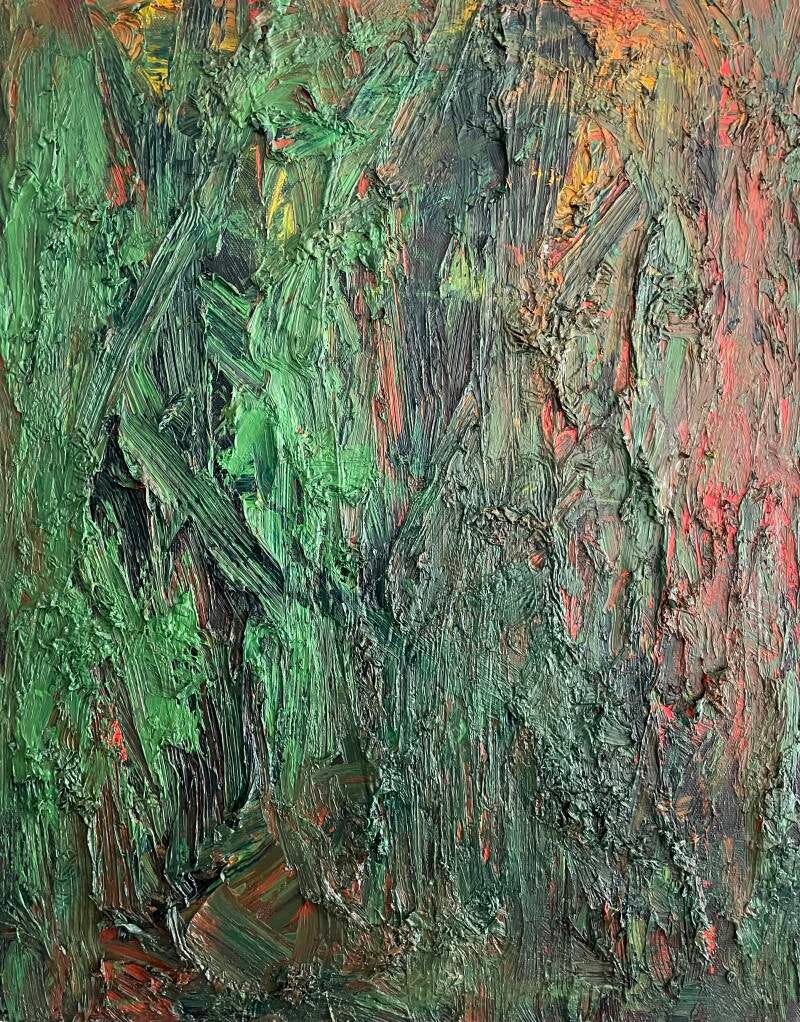

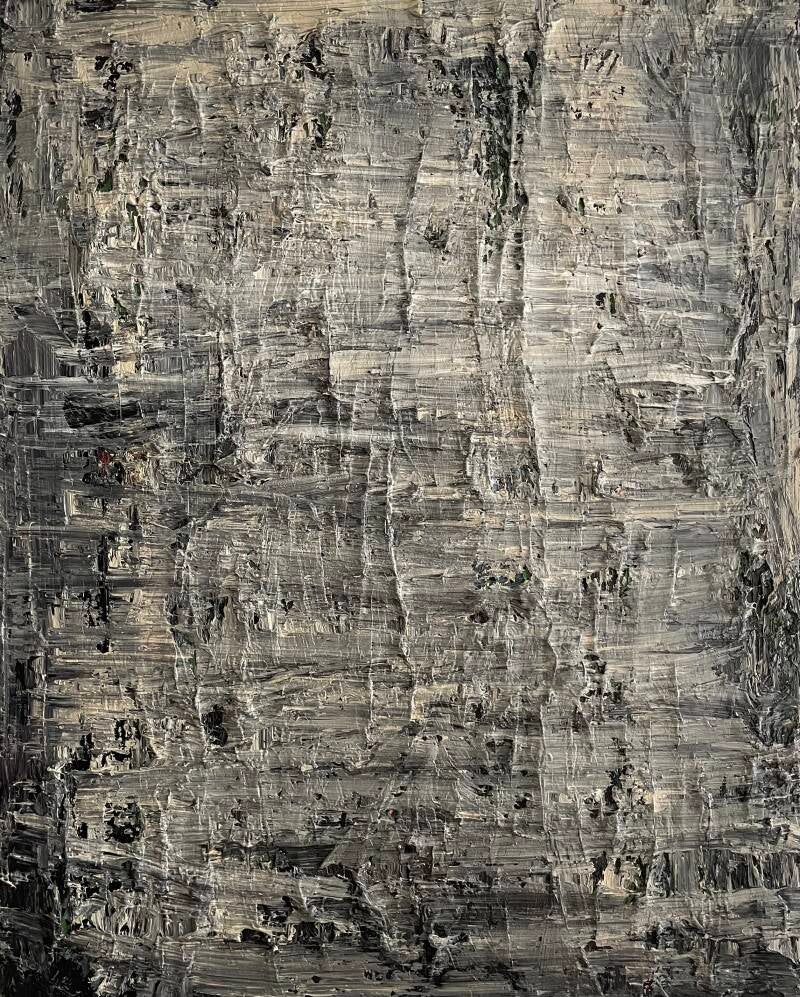

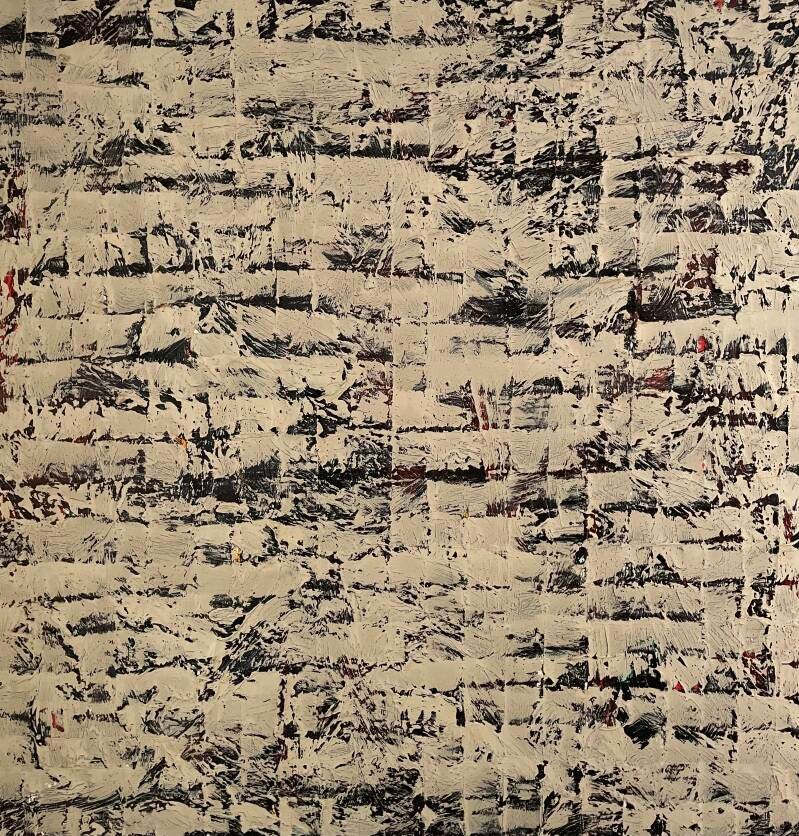

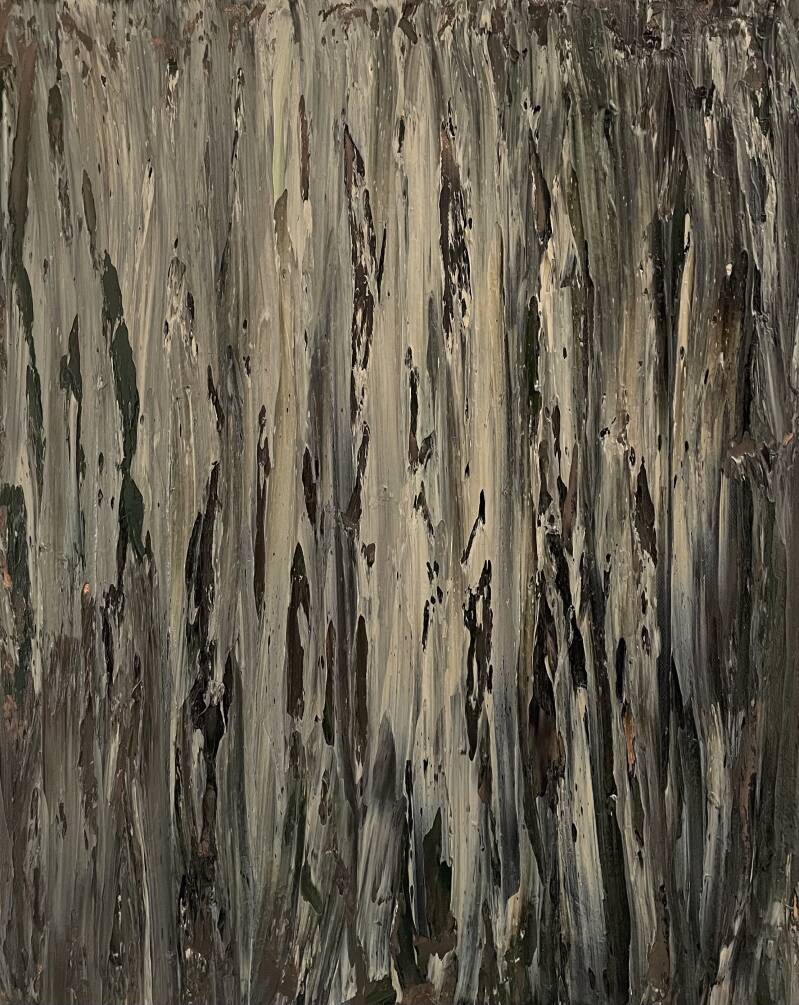

These paintings develop over extended periods, sometimes years. Layers accrue slowly, previous marks visible beneath new gestures. The surface holds time rather than depicting it. Each painting carries the weight of its own revision, a record of decisions made and undone, where what lies beneath continues to shape what appears. Colour and form sediment into one another, creating depth that resists quick reading. I ask for duration — a slowing down, a willingness to stay with what unfolds gradually rather than announces itself.

thinking aloud

like it gritty

quite expressive

keep it light

broken

colours

keep looking

thick

baby blue

beautiful

sweet

bored

in the eye of beholder

cadmium red

white on white

grey

cracking

underneath

original

inner

red image

better than watching TV

layer on layer on layer

see through

true

abstract

tears

without you

won't forget

colours again

small

like a butterfly

square

green

in an istant

sunset

unbleached titanium white

white covering

keep it real

hole

there is always tomorrow

never mind

vertical expression

yellow ochre

why not

formally mad

can no longer hide it

something else

violet

with you

just a thought

voilet with white

sunrise

scarlet wound

red

is real

Sedimented Time

The Palimpsest Condition

These paintings are not made from nothing. Each canvas arrives already marked—bearing the physical residue of previous works, previous decisions, previous failures and provisional successes. They are reworked surfaces, not blank ones. The paintings carry their own archaeological record: strata of pigment, texture accumulated through repeated application and partial erasure, the literal weight of time made material.

This is not incidental to their meaning—it is their meaning. The palimpsest condition of these works offers a counter-proposition to the mythology of the blank canvas, the heroic gesture, the painting that springs fully formed from artistic will. Instead, these works insist that all making is re-making. Every mark is laid over another. Every surface is inherited. And crucially: the return to a canvas is often a return to something unresolved, something that didn't hold, something that failed. The layers are not accumulations of success but of productive uncertainty—each one a response to what wasn't yet working.

In this sense, the paintings enact sedimented time—the way that the past is not simply behind us but beneath us, constituting the very ground on which we stand and from which we act. These canvases make that sedimentation visible, even tactile.

Historicity and the Burden of Form

To paint abstractly in 2025 is to paint after abstraction. The gesture arrives pre-loaded with a century of meaning, controversy, and institutional baggage. The bold stroke cannot be innocent—it carries the ghost of Abstract Expressionism. The monochrome field cannot be neutral—it remembers Malevich, Reinhardt, Klein. The textured surface cannot escape its debts to Rauschenberg's combines or Kiefer's material accretions.

These paintings know this. They are made with this knowledge, not despite it. Their historicity—their awareness of their own belatedness—is not a limitation to overcome but a condition to inhabit. The question they pose is not 'how can abstraction be original?' but rather 'what does it mean to continue?'

The answer, enacted across this body of work, is that continuation is itself a form of meaning. To return to a canvas, to layer new marks over old ones, to refuse the finality of completion—this is to treat painting not as production but as process, not as statement but as ongoing negotiation with form, material, and history.

Against Erasure

There is a politics to accumulation. In an era that increasingly favours the clean slate—the disruptive innovation, the platform that renders the previous obsolete, the perpetual present tense of the algorithmic feed—these paintings insist on keeping. They refuse to erase. They build upon rather than replace.

This is not nostalgia. Nostalgia would seek to recover a lost past, to return to some imagined origin. These works do something different: they hold multiple temporalities in simultaneous tension. The past is present not as memory but as material fact—the ridge of paint from a previous session that now inflects the direction of the brush, the colour that bleeds through despite efforts to cover it, the texture that won't be smoothed over.

In this refusal of erasure, the paintings offer a quiet resistance to what the theorist Franco 'Bifo' Berardi has called the 'infinity of recombination'—the endless interchangeability of data, images, and meanings under conditions of semiocapitalism. Against the logic of infinite substitution, these works propose a logic of accumulation: things gather; marks persist; surfaces remember.

Titles as Thresholds

keep it light. keep it real. keep looking.

there is always tomorrow. never mind. better than watching tv.

in the eye of the beholder. can no longer hide it. true.

The titles function as thresholds—not explanations, not captions, but points of entry that position the viewer in relation to the work. They operate in the register of the everyday, the conversational, the almost-overheard. They are knowing without being ironic, direct without being naive.

A title like there is always tomorrow does not tell us what the painting means. Instead, it opens a tonal field—part hope, part resignation, part cliché repurposed into something approaching sincerity. The phrase has been worn smooth by use, yet here it is offered again, laid over the accumulated surface of the canvas as another kind of layer, another sediment.

The titles refuse the hermetic closure of 'Untitled' or the pseudo-scientific distance of 'Composition No. 47.' They insist on a relationship between the abstract visual field and the language we use to navigate our lives. In doing so, they transform abstract painting from a formal exercise into an existential address.

Between Knowing and Searching

These paintings occupy a middle ground that is difficult to name. They are not naive—they know too much about what has come before, about the conventions they inherit, about the impossibility of innocence. But neither are they cynical—they continue to make, to layer, to return to the canvas, which is itself an act of commitment, even faith.

Perhaps the best word is searching. The paintings search across their own surfaces, return to previous decisions to interrogate and extend them, reach toward something that remains unresolved. The thick impasto, the visible brushwork, the sense of accumulated labour—all of this testifies to a process that refuses conclusion. And within that process, failure is not obstacle but engine. The canvas that didn't work becomes the ground for the next attempt. Uncertainty generates the next mark.

The works that results are heterogeneous: some arrive at something closer to beauty, others resist it; some feel resolved, others remain raw. This unevenness is not a failure of consistency but evidence that the outcome is not controlled for. The process is trusted more than the result. And this temporal quality extends beyond the individual canvas to the body of work as a whole. These paintings have been visited and revisited over long stretches of time—some returned to after months or years, some reworked many times over. The different sizes mark different moments of engagement. The collection itself is a durational record, an ongoing form of practice rather than a produced series.

This is not the modernist search for purity or essence. It is something more tentative, more historically encumbered: a search conducted in full awareness that the ground has shifted, that the terms have changed, that whatever is found will be provisional. The paintings do not claim to answer the question of why paint now. They embody it. They proceed without certainty—and that procedural doubt, that willingness to continue without knowing the destination, registers something true about precarious contemporary conditions.

Temporal Abstraction

If we were to name what these paintings abstract, it would not be form from representation, nor emotion from figuration—the standard accounts of abstract art. Rather, they abstract time. They make duration visible. They compress multiple moments of making into a single, simultaneous surface.

In this sense, they might be understood as a kind of history painting—though one that inverts almost every convention of the genre. History painting was large, public, narrative, heroic; it depicted significant events and made them legible. These works are small, intimate, non-representational, uncertain. They depict no event. Yet they are about history—not as content but as structure. The layers of paint are layers of history: marks, scrapings, gestures, coverings, each one an event that the next responds to, buries, partially obscures, transforms.

This raises questions that history painting, in its traditional form, could not ask. What is seen and what remains buried? What systems determine visibility—which histories become History, and which are painted over? The canvases hold traces of what came before, not fully legible but still inflecting the surface. They don't illustrate this problem; they enact it. The viewer encounters a structure of partial visibility: a surface produced by accumulation and selection, where what's underneath shapes what's seen but can't itself be fully accessed. This is not an argument about power and history—the paintings are not didactic, and they remain, after all, paintings. But they create conditions in which such questions become thinkable. The tension between transparency and opacity, between what is shown and what is withheld, rhymes with larger questions about who determines what gets seen, remembered, counted as real.

And in this, the paintings suggest something about the relationship between personal histories—the accumulation of individual decisions, failures, revisions—and larger historical forces that shape the conditions under which any mark gets made.

This temporal abstraction connects the work to broader questions about how we experience and represent time under contemporary conditions. The accelerated present, the collapsed future, the weaponised past—these are not just political or technological phenomena but experiential ones. And beneath them runs a deeper current: uncertainty as a pervasive condition, the sense that stable ground has become unavailable. The paintings, with their layered temporalities, their visible revisions, their refusal of the instantaneous and the resolved, offer a different kind of time: slow, accumulated, sedimented—and honestly uncertain.

To stand before these canvases is to be invited into a different temporal register—one where marks from previous sessions coexist with recent interventions, where the past is not overcome but incorporated, where the present is understood as a momentary surface over depths of accumulated history.

Conclusion: Why Paint Abstract Now

The question is not answered but inhabited. These paintings do not justify abstraction—they practice it, in full awareness of its history, its baggage, its apparent exhaustion. They propose that the 'now' of 'why paint now' is not a moment of crisis to be overcome but a condition to be worked through, layer by layer.

The answer, if there is one, lies in the work itself: in the physical evidence of return, in the accumulated texture that testifies to duration, in the titles that insist on human presence and address, in the refusal to erase what came before. To paint abstract now is not to accept inheritance passively but to wrestle with it—to take history as material rather than monument, something to be worked through rather than deferred to. Each new layer is a challenge to what lies beneath: not erasing it, but refusing to let it settle into fixed meaning. The palimpsest is not preservation; it is transformation. Every gesture both acknowledges the weight of what came before and insists on the right to change it.

This is not reverence for Rothko or de Kooning—it is something more unsettled, more agential. The inherited histories are acknowledged, yes, but they are not protected from intervention. And the aim is not novelty, not the production of something unprecedented that might satisfy the market's hunger for the new. It is something closer to attunement: the familiar gestures and accumulated forms made responsive to different conditions, alive to possibilities that were not available before. The work does not need to be first. It needs to be present.

And present, too, is the artist—not as heroic author but as something closer to witness: attending to what accumulates, holding the tension between emotion and intellect, between critical thinking and material reality. The hand responds to what the surface offers and resists. Feeling and rigour are not opposed here; they move together, each checking and prompting the other.